|

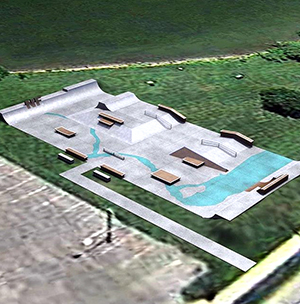

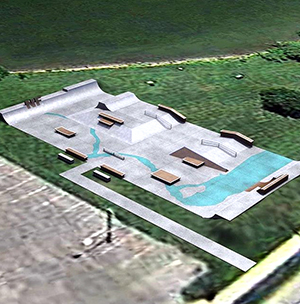

| Computerized rendering of skatepark at Hyde Park next to Sal Maglie Stadium. |

|

|

|

|

|

To hear Niagara Falls Community Development Director Seth Piccirillo tell it, the $10,000 grant the city received from the Tony Hawk Foundation to build a skatepark at Hyde Park was something of a remarkable achievement.

“In Niagara Falls, we took the time to learn best practices, talk to our skaters, put these skaters in touch with residents of all ages and used the Tony Hawk Foundation grant as our blueprint and goal,” Piccirillo said. “Having Tony Hawk associated with a community project is a big deal. It shows our young people that if you get together, build a coalition, petition your government and take the time to plan something special, important people take notice of it.”

Actually it isn’t such a big deal at all. In fact, more than 900 communities across the country, received the Tony Hawk grant prior to Niagara Falls receiving it.

Des Planes, IL, West Bloomfield MI, Monticello MN, Harrisonburg VA, Othello WA, Glen Jean WV, Bellevue PA, Bend OR, South Jordan UT, Gilette WY, North Laurel MD, Bemidji MN, Fairfield IA, Owensboro KY, Houma LA, Aurora IL, Hornell NY, Dublin OH and even tiny Beaver Dam WI have all gotten them.

“We are proud of the grassroots push behind the skate park and thankful for the Tony Hawk Foundation’s help,” said Mayor Paul Dyster. “Our community is collaborating to create a special neighborhood space for our young people. Our partnership will complete a skate park project that has been discussed for decades.”

As is so often the case, the mayor seems to be exaggerating here. Decades? The use of the phrase “skate park” was unknown prior to 1998, just 17 years ago and, even then, it was being used almost exclusively in Southern California where the sport began to take off. No mention of it is found in the archives of the Buffalo News, the Niagara Gazette or the Niagara Falls Reporter prior to the beginning of Dyster’s second term in office, which began just four years ago.

In any event, the $10,000 Niagara Falls grant, like all of the other Tony Hawk Foundation grants, came with plenty of strings attached.

According to its’ website, the foundation’s first rule is that the skateparks, “are designed and built from concrete by qualified and experienced skatepark contractors.”

You know how many experienced skateboard contractors there are on the Niagara Frontier? None.

“If your organization plans to build a skatepark from temporary ramps (steel or wood), it is not eligible to apply for a Tony Hawk Foundation grant,” the guidelines continue. “Your project must be a permanent, concrete skatepark.”

Finally, there is this;

“The foundation may offer technical assistance on design and construction, promotional materials, and other information. The foundation may also facilitate support from vendors, suppliers, and community leaders.”

Hmmm. Which vendors, suppliers and community leaders are they talking about?

Almost as soon as the money came in from the Tony Hawk Foundation, it was turned over to a company called Spohn Ranch, which designs skateparks for pretty much exactly the amount of money the grant is for.

While the Niagara Falls Reporter did not have time over the weekend to look at all of the more than 900 recipients of the Tony Hawk Foundation grants, everyone that was examined had Spohn Ranch do the design work.

And most of them used concrete that was fabricated by companies such as Spohn and its subsidiary TrueRide, which specialize in pre cast concrete components for skateparks.

But Aaron Spohn, president and founder of Spohn Ranch and a close personal friend of Tony Hawk’s, said building skateparks is easy. Educating local politicians is what’s hard, he said.

“Educating municipalities remains the real challenge of our business,” he said. “While we have made great strides in this regard, there are still plenty of cities who want to solve the skateboarding ‘problem’ with the cheapest and quickest solution, rather than investing the time and effort to involve the community in a well-rounded process.”

Educating public officials can be tricky but rewarding, Spohn said.

“We have become very effective with educating cities on how to correctly navigate the skatepark development process so that the end result is an enduring success for both the city and its skaters,” he said. “Rather than being content with dropping some ramps on an abandoned tennis court, we are presenting skateparks as beautiful, aesthetically-engaging works of art.”

Dyster and Piccirillo were apparently excellent pupils.

Neither of them can say with any certainty how many skateboard enthusiasts there are in Niagara Falls. And even Tony Hawk makes no guarantees about the benefits of building a skatepark in a community.

“We do not have any specific studies on the economic impact of skateparks on communities, but from the feedback we receive from municipal skatepark managers, skateparks do seem to have a positive effect on businesses in the surrounding area,” he said. “When a skatepark opens, it tends to draw folks from the outlying communities to come bring their kids to the skatepark, do some shopping, maybe have lunch, buy some gas, etc.”

Tony Hawk, Spahn Ranch and True Ride are all located a few miles from each other in Los Angeles, the center of the skateboarding industry. Skateboard enthusiasts in Southern California benefit from weather that allows them to participate in the sport 365 days a year, unlike Niagara Falls, which gets only 157 sunny days per year, with roughly half of those coming during the long winter months when the ground is covered in snow and skateboarding is not an option.

The minimum cost for a small skatepark of around 4,000 square feet seems to be around $100,000. Dyster is prepared to spend that without knowing how many individuals will use it, or what the economic impact of the city might be.

The money will come out of city’s most recent Community Development Department budget, which comes from federal sources, including the Community Development Block Grant program.

Ironically, the skate park will be built adjacent to Sal Maglie Stadium, a baseball facility that is now in such a state of disrepair that the Niagara Power baseball team recently told the city it can no longer play there.

Why maintain the recreational facilities you already have when you can build new ones? Such is the Dyster approach to sports in the city.